-

- 931

- plays

-

- 385

- listners

-

- 931

- top track count

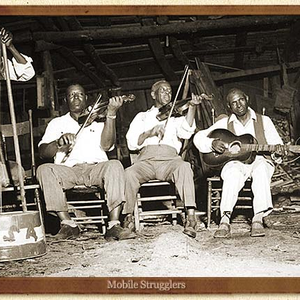

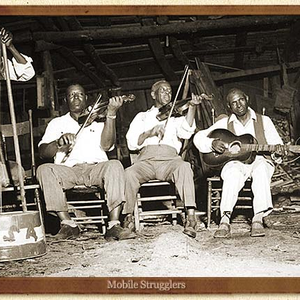

The Mobile Strugglers & The Louis James String Band American Music AMCD-14 Two black groups, one from Alabama, the other from Louisiana, one exuberant, the other more consciously restrained, separated in recording time by fifteen years. Violin, guitar and bass are the core instruments in common, but despite the inclusion of Memphis Blues in the repertory of both, there is little otherwise to bond them stylistically. And although a small-print cover logo promotes this release as 'The String Bands', in reality the two groups sit side-by-side merely for convenience of running time. The bulk of the Mobile Strugglers material makes its public debut here. Of their seven titles the only coupling issued near to the date of recording - on a 78 rpm disc with a pressing of fewer than a hundred copies - was Fattening Frogs for Snakes (surely the weirdest occupation ever to be immortalised in wax) and Memphis Blues. These have been available in reissue for many years, on 'The Country Fiddlers' (Roots RL-316), but it is a pleasure to hear them with improved sound. And it's a delight and a wonder that material unheard outside of the collector's purview for nearly half a century should continue to surface. All the Louis James trio items were formerly available in a ninety-nine-copy-only pressing (to avoid paying UK tax), and presumably there were no further out takes. Everything here, then, is as rare as the proverbial hen's teeth. Items in their repertory such as Don't Bring Lulu and the marches (Bill Russell's notes inform us they played at least one other, which he declined to record) place the Mobile Strugglers firmly within the serenading street combo mould also ascribed to Louis James' trio by Reg Hall's notes. Too few groups which fall into this category have ever been recorded. To augment the picture, however, the eclectic repertory - straight blues, rags, marches, popular songs of an earlier era - may be compared to that of the vibrant ensemble of Blind James Campbell and his Nashville Street Band on Arhoolie 1015, a long standing favourite album of this reviewer. Like Campbell's aggregation, the Strugglers' line up was fluid from gig to gig. One wonders, however, how players from Mobile and Montgomery, over a hundred miles distant, came together to form a viable band. Most tracks feature twin fiddles which weave majestically in and out of one another. When one of these fiddlers, James Fields, is singing lead vocal on Memphis Blues, the second continues playing the harmony line, which provides a clear opportunity to examine some of the creative processes governing seconding. This man, Charles Jones, plays with a clean tone and long bow strokes, compared to his shuffle-bowed cohort at any rate, and proves himself to be a fairly adventurous player on occasion. Some of his high contrapuntal lines, on Don't Bring Lulu in particular, don't quite stay within the key boundaries. Far from sounding excruciating, however, this actually heightens the excitement. Cornfed Indiana Gal stylistically has much in common with the extensively recorded Mississippi Sheiks. The fiddler (probably Jones in this instance) even achieving a tone remarkably similarly to Lonnie Chatmon at times. Tracks which add mandolin to the line-up serve to reinforce the impression, sounding a lot like the Sheiks when Charlie McCoy augmented the group. James Fields was born in 1887, while Louis James was three years his junior. Although a mere hundred and fifty miles separate Mobile and New Orleans, stylistically these two players were worlds apart. Fields was chunky and earthy with a choppy bow; James altogether more restrained and sweeter, and with longer strokes. Reg. Hall makes much in his notes of not having influenced the choice of material at the session, but admits to requesting tunes for those specifically nineteenth century dance forms, polka and mazurka, which 'didn't ring a bell with them.' And one wonders whose decision it was to replace the standard guitar with banjo on the unnamed quadrille tune. Given the older pedigree of both dance form and instruments the banjo was presumably deemed more 'authentic.' And James is clearly pulling the tune up from the depths of his memory, for he stumbles awkwardly at times. Guitarist Ernest Roubleau is consistently solid, and has some nice fill-in runs on Rose Room, a more modern tune than the collectors evidently hoped for within their 'play what you like' brief. The bass, played by August Lanoix, is fairly low-key and unobtrusive throughout. In fact, there is little opportunity, or desire apparently, for any of the trio to let rip after the more usual New Orleans fashion. James switches to clarinet on Exactly Like You, but there is none of the fire of George Lewis or Sidney Bechet. In fact, his style closely follows that of his violin playing, with few frills and a go-ahead melody line. Despite the inclusion in the repertory of Goofus, a hot number beloved by jazz-tinged hillbilly bands, such as the Cumberland Ridge Runners, and Western Swing combos alike, the trio is as laid back during this as in everything else. And therein lies both the charm and historical importance of this session. With regard to musical development in New Orleans it goes some way towards bridging the gap between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, between military and jazz bands, between the Sunday bandstand concert and the Kitty halls, between uptown and downtown. It's a format that has seldom reached disc, and is all the more valuable for that. Reg Hall bares a portion of his soul within his section of the informative contextualising notes, admitting his misjudgement regarding recording venue, and expressing regret for not asking as many pertinent questions as later sprang to mind. I find such open honesty refreshing. All researchers are fallible, but not many of us come right out and admit it. In some ways the stylistic disparity I mentioned at the top of this review actually gives the CD a dualistic appeal, offering invaluable material for those who enjoy the likes of, say, Martin, Bogan and Armstrong, and for more open-minded jazzers alike. It may be that listeners who revel in the disparate twin styles will be few, but that hardly matters. This is surely an essential purchase for those with a foot in either musical camp. Read more on Last.fm. User-contributed text is available under the Creative Commons By-SA License; additional terms may apply.